Falling Farther, Faster: Why Our Boys Are Struggling

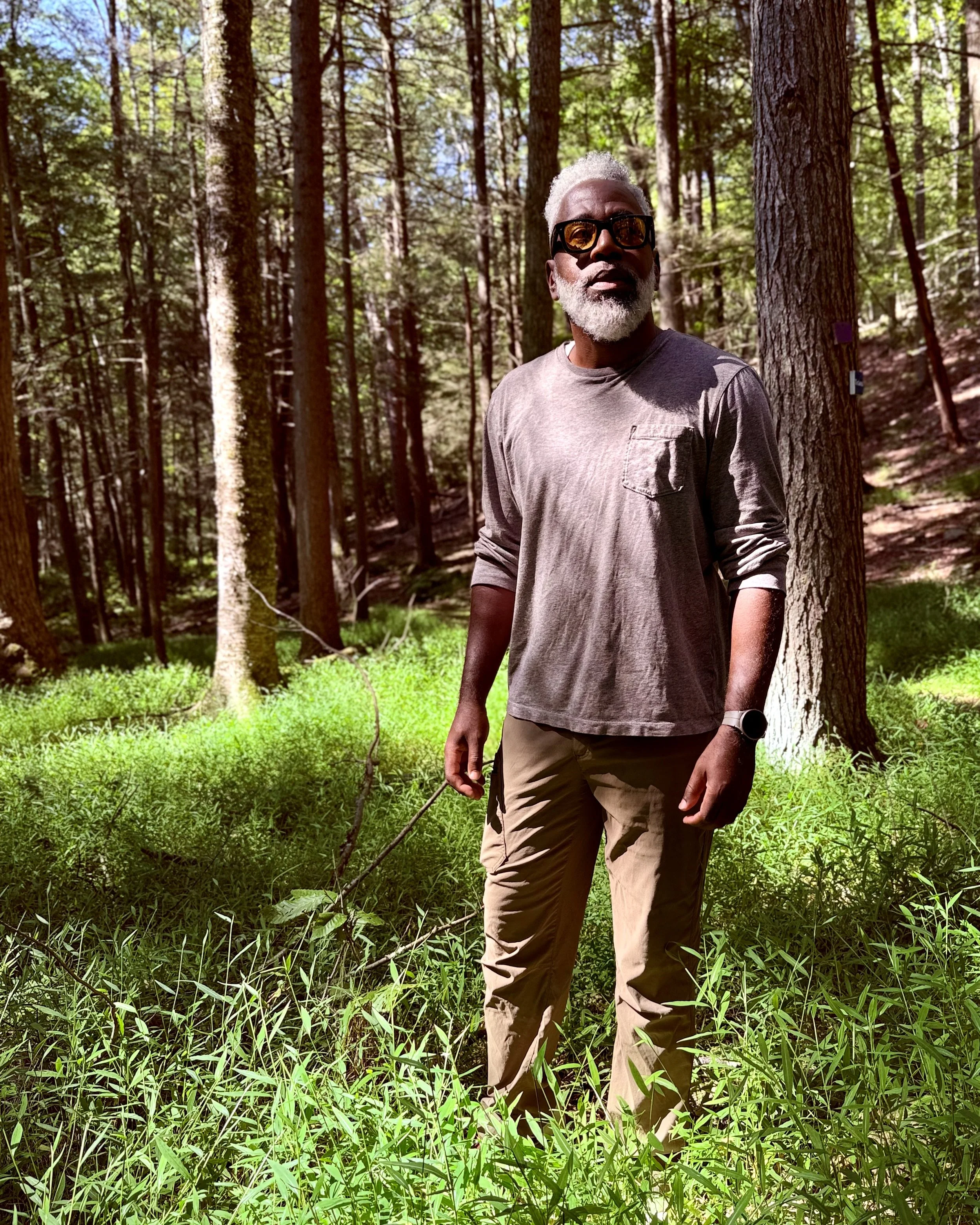

Camping to Connect participants at Harriman State Park, NY

“The most dangerous person in the world is a man that is broken and alone.”

This line has stayed with me for months. Not because it’s dramatic, but because it speaks plainly to a reality we see every day: boys and young men in America are struggling in ways the headlines only partially capture. Beneath the statistics; rising diagnoses, school pressure, disconnection, there is a deeper story about belonging, identity, and what happens when young men lose their place in the world.

Across the country, adolescent mental health is deteriorating at a staggering pace. Nearly one in three adolescents has been diagnosed with anxiety. One in ten has experienced major depression. Autism diagnoses have skyrocketed from one in 2,500 to one in 31. ADHD diagnoses rose by a million in just six years. According to recent reporting, children are meeting school already stressed, overstimulated, and emotionally exhausted; long before they hit middle school. Childhood has been reshaped into something narrow, hurried, and unforgiving.

For boys, this pressure hits differently. Their brains mature later. Their need for movement, experimentation, mentorship, and emotional outlet often collides with rigid academic structures and adult expectations. Many lack consistent male role models at home or in school. Many navigate adolescence in isolation, tethered to devices instead of communities. And with economic mobility stalled for their generation, stagnant wages, rising costs, limited job pathways; many young men simply feel stuck.

The result is a loneliness epidemic that attaches itself to everything else: anxiety, depression, school avoidance, risky behavior, identity confusion, and the quiet sense that they do not fully belong anywhere.

But here’s the thing: solutions do exist. They just don’t show up as quick fixes, viral trends, or new diagnostic categories. They show up in spaces where young men are invited to connect, reflect, and be seen.

They show up in belonging.

The need beneath the noise

Behind every statistic is a young man trying to make sense of himself in a world that moves faster than he can process. Many boys describe feeling unseen in school. Others feel pressure to perform, behave, conform, or mask emotions they don’t have language for. And when boys do ask for help, it’s often after they’ve reached a breaking point.

One youth told me recently, “It’s like everyone expects us to be fine, until we’re not.”

The cultural narrative around boys hasn’t made it easier. For decades, whenever issues facing young men surfaced, the response leaned toward blame, not understanding. Yet the deeper truth is simple: boys need community as much as anyone else. They need mentors, peers, role models they can relate to, affirming environments, and pathways to identity that aren’t built on comparison or quiet suffering.

What they don’t need is more shame.

What they don’t need is more isolation.

What they don’t need is to navigate this alone.

A quiet shift in culture

Recently, something unexpected has emerged on social media: the “quarter-zip movement.” On the surface, it looks like a fashion trend, young Black men trading streetwear for a preppy staple. But beneath the playful videos is something more interesting: young men experimenting with identity, self-presentation, and belonging on their own terms. Young men looking to “level up.”

When a 21-year-old says a quarter-zip makes him “stand straighter” or feel “more put together,” he’s not talking about fabric. He’s talking about possibility. About access. About reshaping how he sees himself and how the world sees him. In its own small way, the movement signals what so many boys hunger for: a sense of maturity, dignity, connection, and legitimacy.

It’s not about the garment. It’s about the permission to rewrite who they can be.

And that’s the same need we hear at Camping to Connect on the trail, around the fire, or inside group conversations: the need for a version of manhood that honors vulnerability, ambition, joy, softness, strength, and community, not just survival.

Belonging as a protective factor

Here’s what years of research and lived work with youth reveals:

Boys don’t heal in isolation. They heal in community.

Belonging is one of the strongest protective factors against anxiety, depression, and self-harm.

Movement and shared challenge regulate the nervous system.

Mentorship strengthens identity.

Honest conversation gives language to emotions boys were never taught to name.

And nature; quiet, unpoliced, and unhurried, provides a backdrop where young men can finally exhale.

At Camping to Connect, we see this every season. On a trail, titles fall away. Status disappears. The noise of expectation quiets. Young men look each other in the eye. They laugh. They reflect. They step into leadership roles; timekeeper, navigator, encourager; that show them what they’re capable of. They share stories they’ve never told anyone. Not because we ask them to perform. But because community makes it feel safe enough to be real.

Camping to Connect currently serves young men from New York City, Colorado’s front range, and Newark, NJ through a network of volunteers, community partners and collaborations.

The deeper crisis beneath the surface

It’s tempting to think the mental-health crisis among boys is about screens, or school, or even the economy. But the deeper issue is environmental: we have removed too many of the structures that once helped young men form identity, purpose, and community.

We’ve stripped childhood of play.

We’ve buried boys under metrics.

We’ve replaced physical exploration with digital simulation.

We’ve rewarded silence over expression.

We’ve disconnected young men from adults who can guide them, replacing them with a Manosphere that keeps them on edge, fostering anger and a victim mentality.

We’ve narrowed belonging to the point where many boys don’t know where they fit.

This is why we see such high levels of despair. This is why so many boys internalize failure or retreat into isolation. This is why emergency rooms are seeing spikes in adolescent mental health crises, recreational drug abuse, and high suicide rates. And this is why meaningful intervention must go deeper than therapy sessions or new policies.

Young men need places to feel human again.

They need community.

They need connection.

They need belonging.

They need mentors.

A path forward

Belonging is not soft work. It’s structural work. It’s justice work. It’s human development work. And it requires intentional space; whether that’s in schools, community centers, barbershops, parks, or on mountain trails; where young men can practice presence, responsibility, emotional honesty, and connection.

When we create these environments, we see transformation:

A young man who arrived silent begins to share his story.

Another who carried shame begins to see his own dignity.

Another who thought he had no future starts to define one.

Another who felt alone realizes he never truly was.

That is the power of belonging.

And that is the foundation every young man deserves.

Professor Galloway said it best: “Everything meaningful in life is about others. Nothing profound is achieved in isolation.”

If we want boys and young men to thrive, not just survive, we must build communities that remind them, again and again, that they matter, they are seen, and they belong.

If you feel compelled about being part of the solution, please consider donating to Camping to Connect, a BIPOC-led nonprofit organization addressing teen social isolation by creating deep, in-person connections in nature.